Irene Rowland MS, NCC, LPC

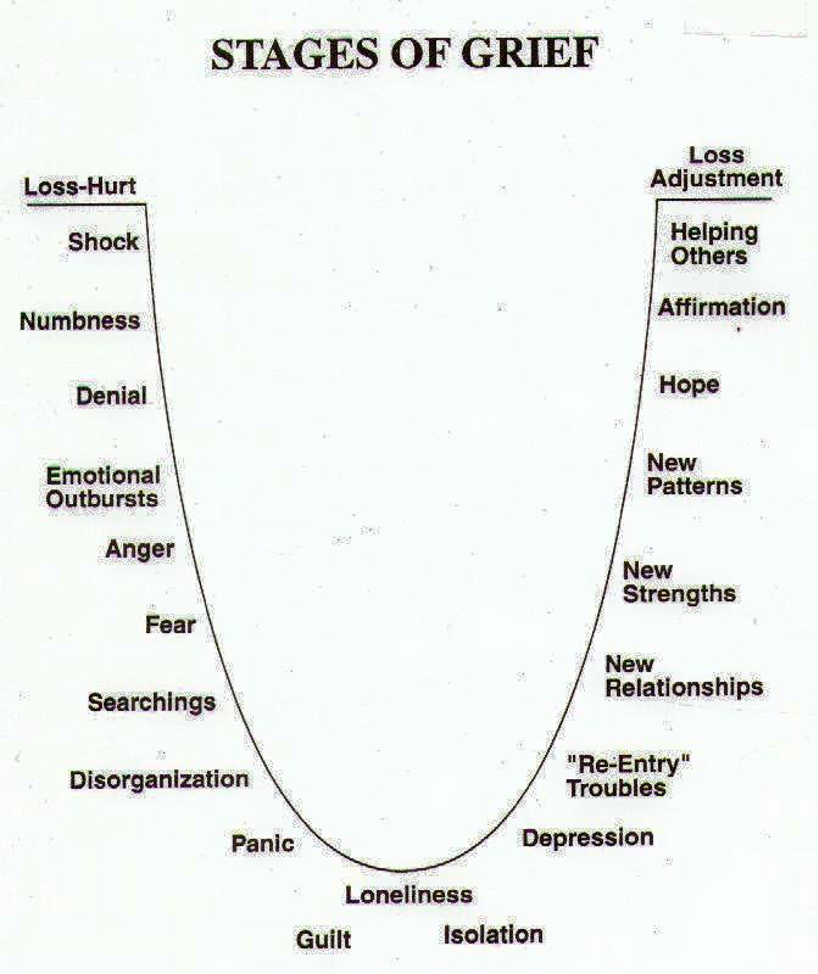

There are many models for the stages of grief. The horseshoe shaped diagram is my favorite and I believe it to be the most realistic. Grief is not linear. People do not proceed through each stage in a neat, orderly fashion. Typically, stages are sometimes skipped and then returned to later, as well as stages being returned to multiple times. This can happen long after a person thought they had worked through that particular stage. Just as the traditional 5 stages of grief by Elizabeth Kubler Ross are not a simple progression through the steps, neither are the many steps in the horseshoe model. If you drew a continuous line of how the steps might go for an individual, you would see that with all the jumbled directions going across and up and down the graph, it would look like a bunch of tangled thread. For many, that’s what grief really looks like.

The Descent of Loss

It can be a slow descent or a rapid plunge to the depths of grief. As stated already, we may or may not experience all of these stages and not necessarily in the order shown in the diagram. The tumble down to loneliness, guilt and isolation can be quite rough which almost makes those lows look restful compared to what it took to get there.

Shock, Numbness, Denial

It’s typical to be in a bit of a fog after you get the news of a significant loss, whether that’s of a loved one’s death, a job loss, a serious health diagnosis or any other kind of change that could be considered life changing. Grief is a natural response to the loss of how you thought things would continue to be and the future you expected.

Emotional Outbursts, Anger, Fear

Grievers can be easily triggered. Some losses are traumatic. With trauma, often

there is hypervigilance. The fight or flight instinct is revved up, as though we must

be on the lookout for any impending dangers at all times. We have all experienced

reactions from people that seem disproportionate to a situation. These emotional

outbursts are sometimes due to grief. The increased levels of cortisol when a

person is in this escalated state of vigilance causes a lot of wear and tear on one’s

body and mind. As a result, anxious, angry, or fearful people are perpetually

emotionally and physically drained. This of course can lead to impaired judgement

and become a vicious cycle. When there’s an anger response to grief, it can be

directed toward others or oneself. Anger turned inward is one of the definitions of

depression. The anger is sometimes directed toward the person who died, the boss

who did the firing, the spouse who left or sometimes toward those who played

“supporting roles” because it’s too difficult to be angry with the source of our angst.

Fear drives the thoughts and beliefs of some of the irrational actions and behaviors of a person experiencing a significant loss. A typical piece of advice after a significant loss is to wait at least a year before implementing any big changes such as moving or a change in career. Part of the reasoning for waiting is that the individual will be further along the healing path which usually means that fear is not as much a part of one’s reasoning process.

Searchings, Disorganization, Panic

Trying to make sense of our pain, of the unexpected tragedies, of man’s inhumanity to man, or any number of other baffling incidences in life, is also a natural reaction. We often feel we can bear a crisis more easily if we can find some purpose in the suffering. Of course, there can be redemption in suffering, miracles can occur in disastrous situations, good can triumph over evil and all of this can be appreciated in retrospect. It is often quite difficult to discern any of this in the midst of the difficulties. Further down the road of one’s healing journey, these treasures can be discovered. I have found that the person who grieves must discover these on their own, rather than having others point them out, because they only sound like empty platitudes coming from others.

Disorganization is part of the mental fog and lack of clarity during the depression of grief. Often a person in this state may be unsure of the day of the week or even unclear of the status of the basic things that they normally could keep track of, such as whether they remembered to take a shower or eat lunch. It can be very confusing to find oneself acting and thinking in ways that are so untypical of the usual way of doing things. Often the energy isn’t there to even be concerned about the discrepancy of who they knew themselves to be and who this stranger in the mirror is now. Panic can set in when this disconnect is truly realized. There can be a fear that the old familiar self may not reemerge. Panic can be the answer to all the unanswered questions of what the future might hold. There can be the fear that things will always be this disjointed and hard to understand, that life as one knew it, is gone.

Guilt, Loneliness, Isolation, Depression

The situations and emotions that grief entails often bring a person to their knees. This is at the bottom of the diagram in the pits of despair. Guilt can color many of the questions we ask ourselves and sometimes there’s a continuation of attempting to blame others and to lay the guilt on their heads. We often have grandiose ideas of our own power to be able to cause certain situations that were actually out of our control. Likewise, we can also assign more power to others than they are capable of having and thereby believing they are at fault in some way in a loss situation. We have all heard absurd news claims that a particular person, country, gender or ethnicity is at fault for a situation when the truth is there are many factors that play into most situations. Loneliness and isolation can breed

depression. Sometimes we make matters worse by intentionally shutting out the rest of the world. Time alone and loneliness are not the same thing. We need solitude to think things through, regroup, reflect and recharge. I say that as an introvert. An extrovert gets their energy from those around them, so in that case they may regroup and recharge better with the support of others, talking through their concerns in their grief journey and thereby processing their thoughts aloud. Isolation during grief can also be a protective mechanism against having to put on a mask and acting as though you are doing better than you actually are. Isolation means not having to answer people’s questions of how you are doing or having to deal with all the things people say as an encouragement which turn out to be the opposite. This can put the griever in the awkward position of being cordial when they really want to scream.

Re-Entry Troubles

If a person stays on the perimeter of life for too long when there’s been a big loss, it can make re-entry more difficult. It is almost as though time stands still for the griever, but the world has moved on and you don’t quite fit in now. Things that were once important to you may now seem trivial. The latest movie, fashion trends, and the current gossip are all pretty insignificant now as compared to whatever importance you may have placed on them at one time. It’s all temporal and often grievers become larger picture type thinkers. Much is trivial when you’ve experienced the degree of brokenness that you didn’t know was even possible prior to your loss.

New Relationships, Strengths, Patterns

After a major loss, there’s a lot of reevaluation that comes out of the experience. We think differently. We see differently. Often there’s a new thirst for life because we’ve developed a new appreciation for the gifts that still remain. New relationships may come from a support group that helped you weather the storms of your trial. You might decide to use the time you have ahead of you to learn new things, catch up on your bucket list, resurrect old hobbies or any number of ways we can regenerate ourselves. All of these options could involve new people in our life and new ways of doing things. Strengths can develop from weaknesses. Surely, the difficult stages preceding these more positive ones involved succumbing to weaknesses at times. If our faith is predominant in our lives, we undoubtedly experience that in our weakness, He is strong and carries us through.

Hope, Affirmation, Helping Others

These last stages of grief are part of the adjustment to the “new normal”, the new life without the person, place, career, or situation in which we had such a connection. This is a connection so strong that the loss catapulted us into this grief journey which in many cases eventually ends up also being a growth journey. Most of us are familiar with Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) which can certainly happen with a complicated grief situation. Some of the PTSD symptoms can occur with “regular” grief. Post Traumatic Growth (PTG) is also a possibility towards the end of the stages of grief. We can become more resilient, kinder, more attentive, more in tune with ourselves and others and generally living a life of more depth and meaning. Grievers typically don’t take things for granted as they may once have done. In the midst of the whirlwind of all these stages and conflicting emotions, God can bring beauty out of sorrow, restoration out of pain, and a peace that surpasses all understanding. This is hard to imagine during a time period when we could not envision there ever being anything positive coming out of loss. Often the magnitude of the loss experience feels like our solid ground is shaking and crumbling beneath our feet. We can find our way again and when we do, our losses become part of our life story. They may even be many chapters of our story, but it’s not the entire story. Our grief becomes part of us and can live side by side with life’s joys. There is life after grief and it can still be good.

Photo Credit: unknown source