Stafff

Competency 2: Positive Fraternal Connections

Posted by Dr. Tom Spudic on April 20, 2020

“Faithful friends are a sturdy shelter: whoever finds one has found a treasure. Faithful friends are beyond price; no amount can balance their worth. Faithful friends are life-saving medicine; and those who fear the Lord will find them.”—Sirach 6:14-16

A. The Importance of Fraternal Brotherhood

The development of positive, healthy, and supportive relationships is important for all individuals to strive towards. With the busyness of work, it is easy for friendship to take a back seat. However, being intentional about making time to be with others—especially brother priests--contributes to better health and happiness.

Subsection 8 in the Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests: Presbyterorum ordinis, states: “All priests, being constituted in the order of priesthood through the sacrament of Order, are bound together by an intimate sacramental brotherhood; but in a special way they form one priestly body in the diocese to which they are attached under their own bishop. For even though they may be assigned different duties, yet they fulfill the one priestly service for the people.”

The idea that one priestly body is formed within each diocese is an important aspect that may often be overlooked. In practical terms: priests need to seek to understand each other; extend hospitality, come together for spiritual, intellectual and social purposes, and show care for those who are ill, troubled, or in danger. A genuine, balanced effort to cultivate solitude with the Lord will have a positive effect in relations with others, and especially brother priests.

In 2011, Monsignor Rossetti published a book called “Why Priests Are Happy” (Ave Maria Press). His research found that priests who build charitable relationships with family, friends, and neighbors have a better connection with God. Loving neighbors and relationships help to love God. What does it mean to form charitable relationships?

Charity in relationships begins with being generous with time and energy without expecting anything in return. Are there areas of ministry in which we look for help, or wish others would notice that we are in need? Often the best way to combat these deficiencies in our daily work is through trust and communication. When possible, it can be helpful to remember that just as we have unmet needs and wants, others do as well.

A general guideline which applies to all of life, but perhaps which priests find difficult to live with in regard to each other, is that no one can argue with kindness. Kindness may not always yield the results you would like quickly or exactly as we would like. Sometimes we may find ourselves in situations that cannot be changed, and all we can do is bear with it. Still, it may be difficult to hold anything against someone who is truly kind. That means, then: do not be that unbearable situation to someone else! Life requires lots of give and take, and often much more give than take. Be careful not to be unreasonable in insisting on doing things your own way, and always be ready to go the extra mile to accommodate the preferences – and yes, sometimes the quirks – of others.

The Church sets a vision of the presbyterate as a family. That spirit of give-and-take that we have to develop is in relation to the other members of our family, and we cannot (or should not) simply “opt out” of our family. Our past experiences of our family may often affect how we view our role in our families as adults. Did we get along with siblings growing up? Were our parents fair and just? In our daily interactions with those we are in familial relationships now, what roles do we take? Priestly fraternity excludes no one. However, it can and should have its preferences, those of the Gospel, reserved for those who have greatest need of help and encouragement. Living this family life takes special care of the young priests, maintains a kind and fraternal dialogue with those of the middle and older age groups, and with those who for whatever reasons are facing difficulties.

The grace of ordination “takes up and elevates the human and psychological bonds of affection and friendship.” Living the Gospel presumes spending time with those who have the greatest need of help and encouragement. We cannot choose the family we originate from – and we cannot choose the family that our work and vocations place in our lives. It is wonderful to be assigned with brother priests whom you “click with,” but even when that is not the case, the rectory should serve as a model to other households in the parish. This requires patience, good will, a willingness to grow together, self-knowledge, and a sense of humor – all traits that are needed for successful family life. We do not learn about family life by reading books about families – we learn by living in a family.

Fraternity allows for the celebration of good times and provides support in bad times. While it may be difficult, learning to trust in others, sharing similar struggles, victories, and experiences creates closeness. True brotherhood is taking an interest in the dreams and goals of others and encouraging them then celebrating when these are achieved.

Taking a break from the usual routine of ministerial life can lessen the possibility of burnout. Feelings of loneliness can create or perpetuate unhealthy vices. Having fraternal relationships that allow for us to confide in others can boost happiness, reduce stress, increase our sense of belonging and purpose, improve our confidence, improve self-worth, and help us cope with traumas such as the loss of a loved on. These relationships may encourage positive change such as getting good exercise and lessening harmful habits such as excessive drinking. Research shows that adults with strong social support have a reduced risk of many significant health problems, including depression, high blood pressure, and an unhealthy body mass index (BMI).

Some people that we associate with may spend their time with others complaining and a little venting can be beneficial. According to Jon Gordon, who wrote the book "The No Complaining Rule," the more we complain and the more we surround ourselves with those who complain often, the more unhappy we become. Research has shown that excessive complaining or listening to others complain can develop illnesses such as heart disease, anxiety, and depression. Experts say that children who grew up in a household whose parents complained a lot grow up to be unexpressive of what they feel, unmotivated to act, feel discouraged, and only see the negative. Scientists who study brain functioning have noted that each time a person complains, the brain produces the stress hormone cortisol. This produces rise of blood pressure and glucose spikes. The brain works to rewire itself which means that it makes the same reactions much more likely to happen again. To combat these negative effects, a good solution is to define the problem and then work to solve it. Brainstorming with others could help us get a better perspective. When we develop a problem-solving attitude to combat our negative thoughts, we are empowered to take action or let something go rather than feel helpless or hopeless..

“God sends us friends to be our firm support in the whirlpool of struggle. In the company of friends we will find strength to attain our sublime ideal..”—St. Maximilian Kolbe

B. Self- Assessment About Our Own Sense of Fraternity

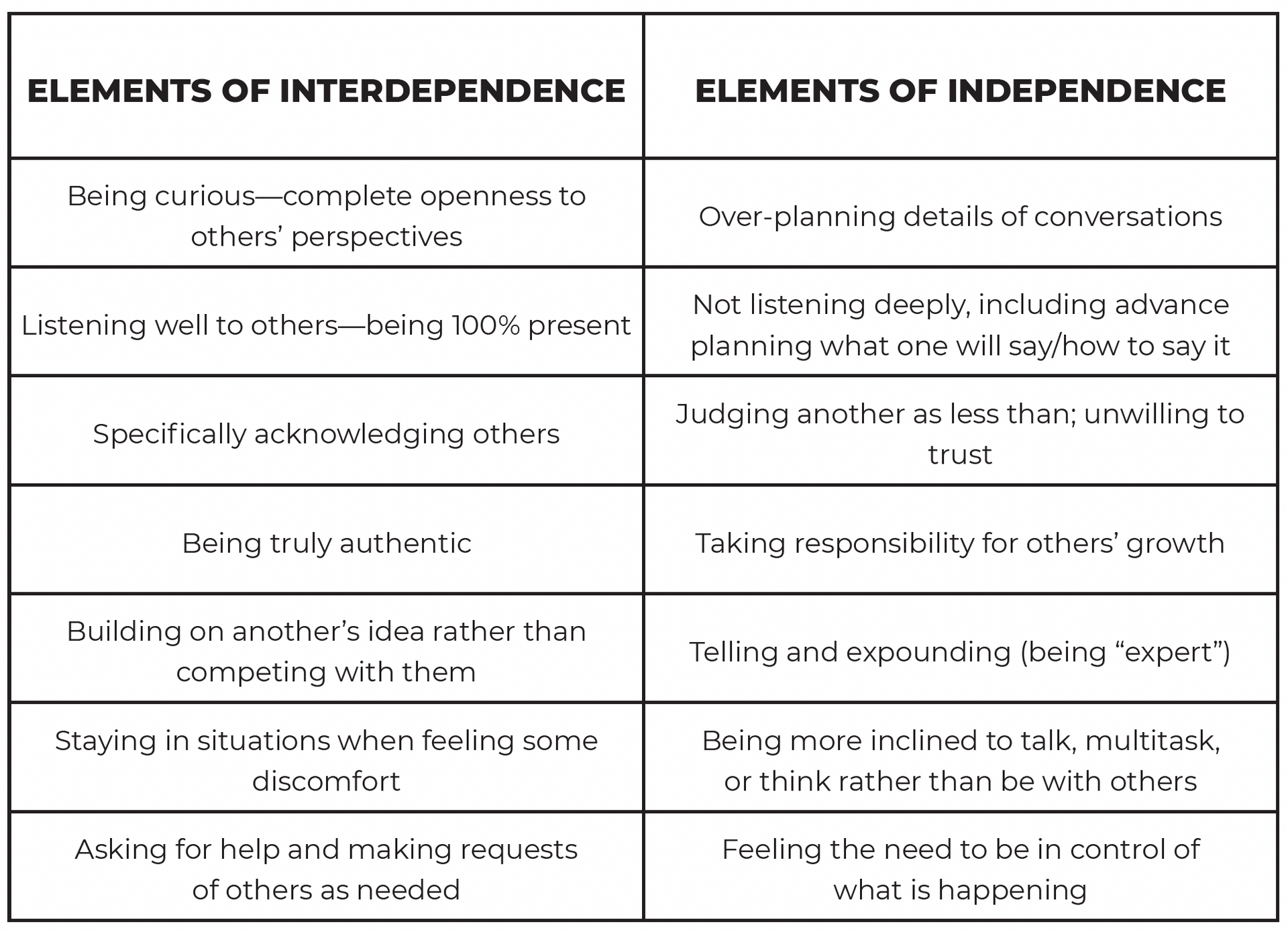

We are often raised to be independent which can be of great service to us; however, it is helpful to remember that being INTERDEPENDENT is actually the best way to stay healthy and happy. Being interdependent helps us to blend differences and can teach us to understand and/or accept other views even when they disagree with ours. Being interdependent is a choice to be curious about others‘ points of view rather than reactive to them. Living too independently can cause us to follow the energy of our own strengths and meet our own needs rather than be aware of others’ strengths or needs.

Consider the following questions regarding interdependence. Do I have a sense of connectedness to other brother priests? Do I have at least one other priest friend who I can all if I get an overwhelming call from a parishioner or need to discuss how best to handle a difficult situation? How often do I call, text, or email? How about see in person?

Reflecting on the characteristics above, how much do I function independently and how much interdependently? Which areas require focus so that I can improve?

C. Tools for Developing Fraternal Connections

Some find it easier to develop brotherhood than others. Experts in the field of relationship building have identified three phases of forming friendships as indicated below:

- Phase 1: The Formation Phase is the transition from strangers to acquaintances to friends. During this phase individuals engage in interactions to get to know each other and to forge the affective bond that characterizes a friendship. Both youth and adults tend to form friendships with others who are like them.

- Phase 2:

The Maintenance Phase involves engaging in interactions that serve to sustain the relationship. Friends engage in a variety of behaviors to maintain their relationship, such as sharing interests, doing recreational or leisure activities together, and exchanging support and advice. Friends typically have conversations about topics such as family issues, other interpersonal relationships, and daily activities.

Of mention regarding the vocation of priesthood is the reality that with changes in assignments comes a change in closeness with those who have lived in the same house and with parishioners. If good connections have been developed in a particular parish, after resettling, there will need to be time for adjustment. Transitions can be difficult, and it is helpful for priests to recognize emotions (e.g. loss, anger, frustration) that develop as assignments change. If there is sadness or a feeling of loss, some time may need to be allotted for grieving. As a way to begin to move forward, openly communicating what future relationships may look like regarding staying in touch and continuing that fraternal bond that has formed is important. Boundaries may need to be established that demonstrate “moving forward” both on a physical and emotional level. The expectation for getting “settled” and feeling more comfortable in a new setting is going to be about a year. - Phase 3: The Dissolution Phase: While some friendships will be maintained indefinitely, others will dissolve or break up. Friendships dissolve for multiple reasons and under multiple circumstances. Sometimes the dissolution can be attributed to circumstances; a friend may move away, and contact becomes harder to maintain. Sometimes friendships end abruptly. For instance, friends may have a major disagreement that is not resolved. Friendships may also end gradually. In some circumstances, friends have less in common over time or feel less supported by each other.

1. Elements of Strong Connections to Others: A Time to Practice Virtue of Charity and Exhibit Fruits of the Holy Spirit.

“A tree is known by its fruit; a man by his deeds. A good deed is never lost; he who sows courtesy reaps friendship, and he who plants kindness gathers love.” —Saint Basil 6:14-16

When we know ourselves well, we know our needs. With the help of the Holy Spirit, we can identify aspects of ourselves that may help us live the fruit of the spirit and be Christ to others. Connection is a 2-way street; others can only honor our needs and wishes if we communicate them. The depth of friendships varies, and by explicitly stating what we are appreciative about to others will help friendship of all types flourish. Lessening our expectations of others and just being present when needed is going to result in less disappointment and more happiness.

Strong relationships require strong boundaries. To maintain good emotional health, we must know our limits of giving and be intentional about adequate self-care. Did your family teach a good balance of work and play? Were you given the freedom to learn and grow? Were you given a good example of respect among family members? Patterns of relating often remain the same even after we enter adulthood if we are not self-aware and intentional about behaving and speaking differently. If we grow up in a home where we often felt rejection, we may hesitate to reach out for help when we need it. As we grow to know ourselves better, we can develop new patterns of relating and let go of the ways that are not as effective.

Holding grudges erodes relationships. We have the opportunity to practice being merciful and forgiving of others. We all struggle at times to be our best selves! Giving grace as God gives grace goes a long way in growing in holiness and helps us to feel better about ourselves.

2. Practical Ways to Find Community with Brother Priests and/or Parishioners—Defining Who, When, What?

The frequency of interactions between friends is one central determinant in the success of maintaining a friendship. Answering the questions below could help you if you need to build better fraternal connections.

- Who do you know? Who do you have things in common with? Who were your friends in seminary?

- What is Your phase in life? Are you young, middle-aged, older? What do you like to do? Do you hike, play golf, run, play tennis, bowl, play poker, go to the movies, gather to watch movies, like reading books, enjoy doing service work? Would you like to start a “club?” Is there a new activity you would like to learn or explore? Is there someone else you would like to ask to join you?

- When is your day off? Can you coordinate to be off the same day as other friends?

- What does maintaining a good relationship with the family you grew up in look like? How much time do you want to give to staying connected with parents and siblings?

3. Elements of Good Communication

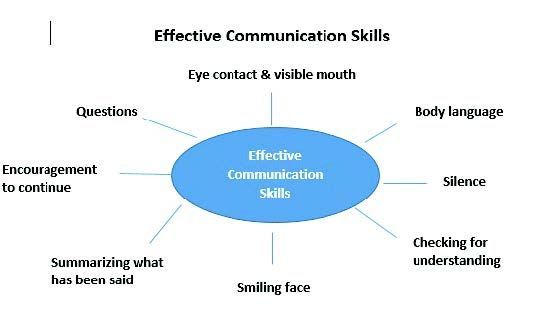

Experiences in our family of origin along with opportunities we have had to learn to communicate as we mature help or hinder our ability to relate well with others. Below are elements of communication that have been determined to be most effective:

Along with these elements are important skills that respect boundaries of others in relationship:

- Be clear, concise and considerate of the time you are speaking vs. listening. Try to keep it balanced.

- Do not ever assume you know what someone else is thinking. Instead, be open and accepting of what the other person is communicating. Ask, “Can you tell me more?”

- Respect the autonomy of other people . . . Ask “Can you help me understand . . . ?”

- Speak with “I think” and “I feel” rather than “You should”New Paragraph

The Priest’s Relationship with His Parishioners

Bishop Michael A. Saltarelli of the Diocese of Wilmington, Delaware says that people are looking for two things in a priest: “to be present and to be pleasant.” In the priestly fraternity, as in the family, relationships cannot be assumed, much less taken for granted. They must be nurtured. In 1 John 4:20, the Beloved Disciple teaches: “If anyone says, ‘I love God,’ but hates his brother, he is a liar; for whoever does not love a brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen.”

The fundamental disposition of the priest, then – and above all, of the parish priest – is toward the People of God. In treating this aspect of the priest’s relations with others, the Council’s Decree on the Ministry and Life of Priests, Presbyterorum Ordinis, states, “Priests have been placed in the midst of the laity to lead them to the unity of charity …. It is their task, therefore, to reconcile differences of mentality in such a way that no one need feel himself a stranger in the community of the faithful. They are defenders of the common good, with which they are charged in the name of the bishop. At the same time, they are strenuous assertors of the truth, lest the faithful be carried about by every wind of doctrine. They are united by a special solicitude with those who have fallen away from the use of the sacraments, or perhaps even from the faith. Indeed, as good shepherds, they should not cease from going out to them. To do this, and to do it well, the priest must know his people.

Presence is the language of love; naturally, we want to be present to the ones we love. However, a priest’s love for his people is directed not at his own longings or self-fulfillment, but rather at leading them to a deeper love for Christ. If the shepherd is going to guide his sheep on the path to greener pastures, guiding them to stay on the path and prodding them to move forward, he must walk in their midst.

Integrity means that the priest works toward selflessness and is willing to suffer for the sake of the truth because the very purpose of his existence is to help his people make progress on the path to eternal salvation. Priests need prudence not to speak words that are rash. When we know people’s struggles, failures, and successes, when we understand their perspective on their deepest desires in life, then we learn when and how to speak, in order to lead people into all truth.*

*(Information taken from https://sfarchdiocese.org/documents/2017/10/priest-relationship-to-the-lay-faithful-rector-conference-march-2016.pdf)

Conflict Resolution: Successful Negotiation of Disagreements Can Foster Increased Trust and Closeness

In general, conflict is infrequent in the early stages of forming a friendship but tends to increase as individuals become closer friends over time. Conflict involves self-disclosure and exposing one’s own vulnerabilities. Evidence suggests that conflict can serve to strengthen the emotional tie between friends.

Going back to our family of origin, we have learned how to handle conflict based on reactions from our caregivers. The diagram below shows 4 boxes. We become Accommodators when our caregivers were very strict. We learned to “do it the parents’ way” and were not usually given an opportunity to have a voice and be asked our thoughts. Some become Avoiders out of a deep-rooted fear of upsetting others. Their environment was dismissive or hypercritical so they deliberately sidestep conversations. Controllers were victims of inappropriate control and have difficulty trusting others. They strive to control everything around them to gain peace. However, in the end, they just feel anxious. Which box do you find yourself most in?

The goals in conflict resolution are to Collaborate and Compromise . . . rather than accommodate, avoid or control. Ideally, we communicate assertively (rather than passively or aggressively) to express our needs. In addition, we are concerned with satisfying others’ needs which results in cooperation. (See the attachment to see qualities of assertiveness vs. passivity and aggression in order to assess if it may be helpful to change your pattern of communicating).

Personality and temperament play a big part in relationships! Being able to respect others’ uniqueness as God’s plan for everyone goes a long way in accepting and tolerating differences.