Staff

Competency 11: The Advent of Stress

Posted by Holy Family Counseling Centers Staff on April 20, 2020

Adventus. Arrival. The arrival of Christ in our hearts, in the world, and into God’s extraordinary plan for our salvation. Th e season of Advent is upon us. With it comes not only the call to spiritual preparation for Christmas, but also the nearly inherent need to manage the stress of the season. We’ve come to expect the bombardment of consumer commercialism, countdowns to Christmas and, as pastoral ministers, the vigilance necessary to keep Christ in Christmas for ourselves and others.

A. Parts Work

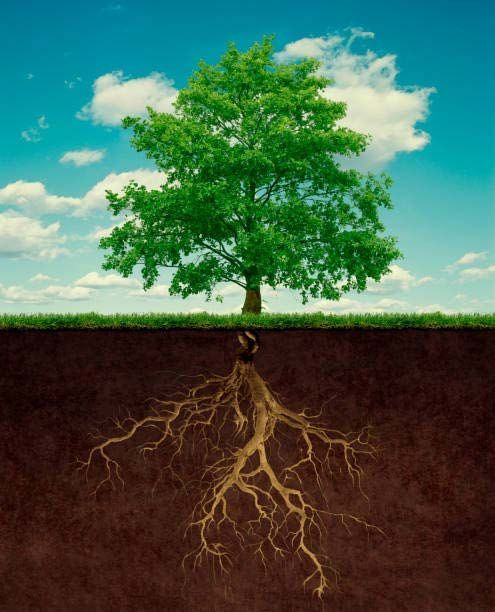

In the midst of this season, priestly formation along with the fruit of spiritual direction has sought to plant seeds of an individual call to personal integration. It is in that sense that we continue to work at bringing together in a psycho-spiritual wholesome manner both the best and the most challenged parts of ourselves. It is precisely this notion of “parts” that is being addressed here. While a unifi ed self is the goal, the implication is that there are “parts” to bring together. It’s not that we’re saying we all have a form of Dissociative (Multiple) Personality Disorder, but rather that we have aspects of our personality that oft en unconsciously are at work, or at war, within us.

At our September Convocation of Priests at Lake Lanier, Dr. LeNoir gave us an introduction to our “ internal family” of parts (Internal Family Systems/ IFS Th eory). He mentioned all of us having suppressed “Exiled”/ wounded/ fragile parts that are protected and controlled by our internal “Managers” and indulged and placated by our “Firefi ghters”. Dr. LeNoir sought to help us understand that these confl icted parts of ourselves are misguided attempts at self nurturing. He tried to assist us to learn that the real goal is parenting ourselves with a Holy Spirit inspired soothing and compassionate love. Ultimately, this is the key to being fulfi lled.

A parallel to IFS is commonly referred to as the Drama Triangle. In this downward pointing triangle three archetypes of our personality are proposed. At the downward point is the role of “victim”. Th e other two points of the triangle are the “Rescuer” and the “Persecutor”. It is important to point out that all the roles in the Triangle are fl uid, i.e. each role may switch and assume the other two roles both internally and externally with others. Whenever anyone in this triangle changes roles, the other two roles change as well.

Not surprisingly, Victims often feel victimized, trapped, helpless and hopeless. They are convinced they are at the mercy of life’s circumstances. Unwilling to take responsibility for their undesirable circumstances, they don’t think they have the power to change their lives and communicate the need to be rescued and often cast blame on Persecutors. If the Victims continue to stay in a ‘dejected’ stance, it will prevent them from making decisions, solving problems, changing the current state, or sensing any satisfaction or achievement.

Rescuers on the other hand constantly intervene on behalf of the Victims and try to save Victims from perceived harm. They feel guilty standing by and watching others suffer. While Rescuers may be well intentioned in their attempts to ‘help’ others, they fail to realize that by offering short-term fixes to Victims, they keep Victims dependent while neglecting their own needs. This is why Rescuers often find themselves pressured, tired, and may not have time to finish their own tasks, as they are busy coming to the aid of Victims.

In this paradigm, Persecutors are like critical parents who are strict and firm and set boundaries. Their tendency is to think that their perspective must win at any cost. Persecutors blame Victims and criticize the behavior of Rescuers without providing appropriate guidance, assistance, or solutions. Skilled at being critical and finding fault, and seeking to control while establishing order with rigidity. They keep the Victims oppressed and sometimes can be a bully.

As in IFS, the goal of working with these parts is inner reconciliation and transformation. The Drama Triangle becomes an inverted Empowerment Triangle pointing upward with the Victim transformed into the Creator at the pinnacle, focusing on outcomes and solution options rather than problems. At the bottom points of this redeemed triangle, the Rescuers become Coaches, who with compassion and faith in the potential of the creator offer goals and action plans. The role of Persecutor is transformed into that of Challenger, challenging notions of the status quo and striving for growth and development.

B. Opting out of the Drama Triangle

The way in which we manage conflict in our professional and personal lives is largely determined by our upbringing and early environments. These early prototypes also determine whether or not we choose to participate in drama and conflict. Do you recognize the victim’s voice saying, “Why does this always happen to me?”; or the Persecutor justifying actions by stating, “If you would have only done what I told you.”; or the Rescuer who is only happy when helping others?

Lack of self awareness can prevent us from realizing the cost of staying in the triangle and how it impacts our well-being and happiness in the long run. The first step in improving how we handle stress in relationships, and within ourselves, is to acknowledge it and take responsibility to change it. Understanding the drama triangle and different roles represented can allow us to identify our own patterns and be willing to change them. Recognizing patterns is not always easy. Think of the last conversation you had where you were sad, angry, or lonely afterwards. Play that conversation over in your head, as much as you can remember. Do you see what role from the drama triangle you were playing? Was the other person also taking on a role, or were they not engaging in the conflict?

We are creatures of habit and develop routines for almost every aspect of our lives. This includes conflict. We respond in similar ways to stimuli that we have experienced before. But we are not beholden to these reactions. By being aware of our roles and responses we can set boundaries with ourselves, and with others, to slowly start to change the patterns that we recognize to be harmful. Psychologist Acey Choy developed the Winner’s Triangle to counteract the Drama Triangle:

Vulnerable. The vulnerable person allows their emotional process when they’re having a rough time, but knows that they have the resources and abilities to find their own path and get their needs met. They can ask for help but won’t take a ‘No’ as a personal slight. They will respect another’s autonomy to set a boundary.

Responsible. A responsible person is a caring individual but rather than enabling dependent behavior, they will encourage empowerment. They will recognise that their help is most effective when showing someone in a vulnerable position that they’re able to stand on their own two feet. They will be able to set healthy and respectful boundaries, being honest about their own needs, and being able to meet them within the responsible role.

Potent/Assertive. The potent/assertive position is someone who actively meets their own needs and drives, but unlike a persecutor, they won’t need to do it at the expense of anyone else. They will be good problem solvers and negotiators, finding a way to meet their needs, without shaming, belittling, or picking on others. When we are able to opt out of the drama triangle we allow ourselves breathing room and the ability to lower our overall stress.

C. Stress Management

Stress is a universal experience. It is how our mind and bodies handle the tasks and situations that are set before them. No one in the history of mankind has been able to escape stress, not even our Lord or his Mother. When discussing strategies for good stress management is it helpful to make a distinction between Distress and Eustress.

Distress is often referred to as negative stress, as this causes our bodies to produce cortisol and somatic responses that put the body in a fight, flight, or freeze mentality. This puts a load on the body and mind from which often is difficult to recover, especially as more distress is added or encountered. Distress typically comes about when we feel a threat to our identity, in particular to how we see ourselves or how we think others see us as “good” (good is quotation due to the fact many people can have different ways of measuring what they need to do in order to be considered good). Many times you can identify when you are in distress when you find yourself engaging in negative self-talk or demanding self-talk. “ I must deliver a homily that changes the heart of my congregation, or else I am not a good pastor”, “ This meeting must go well, or the event won’t happen, and I won’t be the good pastor I feel the Lord is calling me to be.”, “In order to be a good pastor I should know how to love any soul that comes my way”. This negative self-talk comes from the threat that if a certain result is not achieved then my identity as a good pastor, person, or son of God is threatened to be true, which typically can result in a feeling of helplessness and being overwhelmed. As we will discuss below, the ways to combat distress will focus on how to let go of the result of the situation and focus on how to grow.

Eustress is referred to as positive stress. This is the stress you experience when you are trying to improve at something and it pushes you to keep getting better. For example, studying for a test in order to gain a better understanding of the subject material, or working on developing skills like playing an instrument in order to develop your musical abilities. This is typically positive because it provides motivation and drive without invoking the intense somatic response that is associated with distress. Eustress is typically influenced by our ability to perceive an opportunity for growth rather than a threat to our fundamental identity. One can tell that he is experiencing eustress from the self-talk he has which typically recognizes limitations, is adaptable, and focused on the next step rather than the result. . “I hope that I am able to help people understand the importance of Christ. I would like to share with those I can, the incredible gift of Christ becoming incarnate”, “ I have high hopes for the event going well. If we experience hiccups along the way, I will use them as an opportunity to learn how to plan the next event”, “I would love to be able to help this soul, however, I am not sure what would be the best course of action. I would like to consult my friend on how he would recommend the process”. This self-talk allows the person to recognize that it is okay to have limitations, while not allowing the limitation stop him from growing and developing insights to give a better homily, prepare for events, or how to be attentive to individuals. It allows the person to recognize the value that they are good not because of the result they are able to produce but rather because of the gift God has given them to be able participate in his work. This is reminiscent of the quote from St. Mother Teresa “God has not called me to be successful, He called me to be Faithful”.

A helpful framework to keep in mind when managing stress is to focus on how you cultivate restoration and rest versus distraction and vegging out. Restoration helps the person transition from distressing task by providing themselves w/ a space that allows them let go of the distressing task/ situation, This can include things like prayer, honing skills like: playing an instrument, wood working, art, writing, or other creative means, and spending time with close friends, and exercise. Rest is important as sometimes our minds and bodies need a moment of quiet and silence. This helps the person receive some time to recharge and be able to face stressful situations again. Some helpful resting strategies included allowing yourself to have some alone time, sleep, being outdoors, and to do mindfulness exercise (examination of body and mind). The key to rest is allowing yourself to receive and listen to your body and mind. While in restoration we allow ourselves to focus on continuing to develop skills while giving ourselves permission that we don’t need to have everything accomplished today. Distraction and ‘vegging’ are typically not as helpful when dealing with distress. It may help to quiet the negative self-talk for a moment, but it comes back later. When handling stress we want to help ourselves promote a mentality of St. Pope John XXII, “Lord, it is your Church, I am going to bed”.

As we prepare for the arrival of our Lord, it is good to remember that Mary and Joseph faced their own stresses as they prepared for the birth of our Savior. Stress is completely natural. We owe it to ourselves to face the adversity that causes our stress and prepare ourselves by accepting who we are, recognizing our patterns and committing to change.